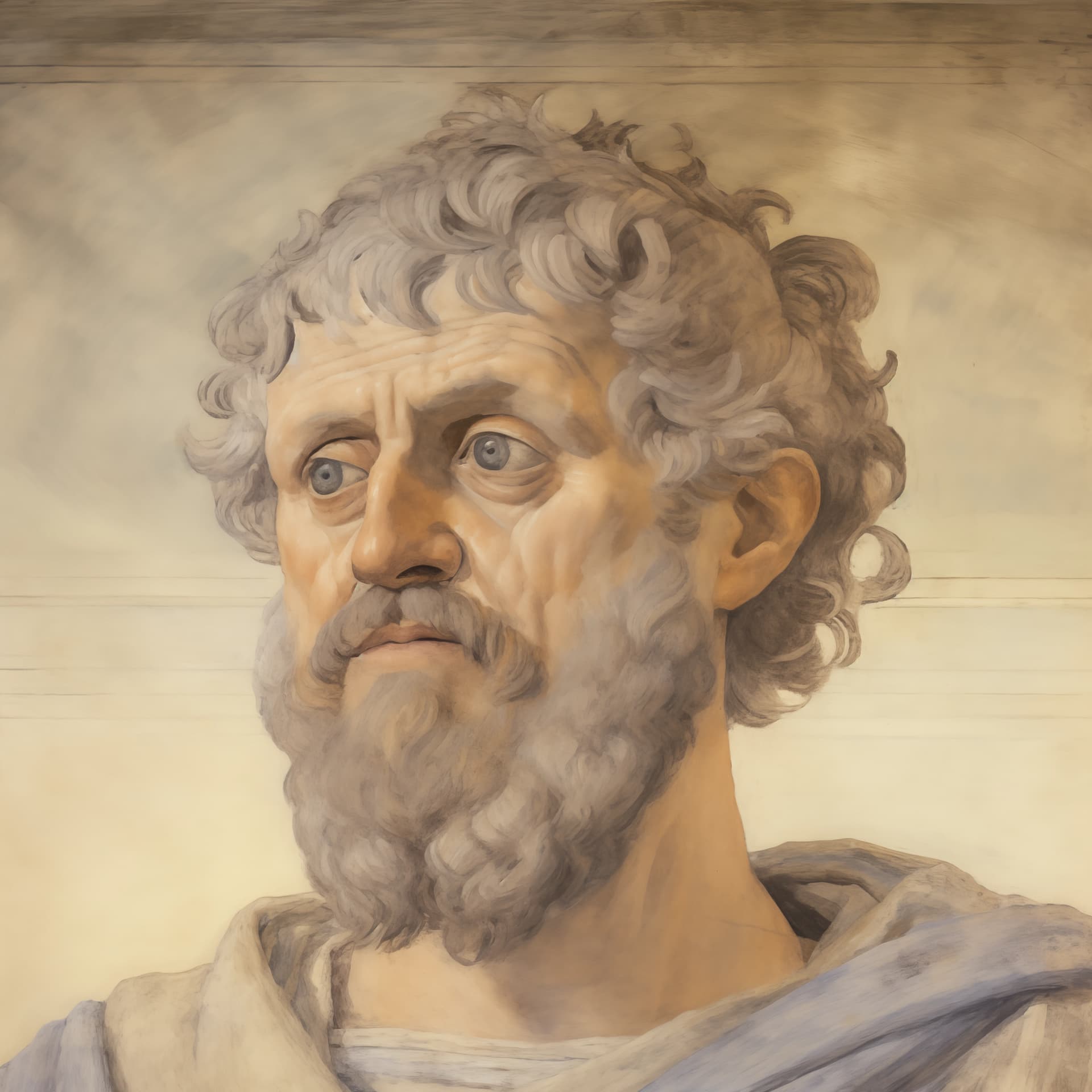

Proclus

Philosopher

Proclus was a late Greek philosopher and an incredible practitioner of the ways of the Gods. He became a magnificent High Priest and major patron of the city of Athens, a feat that is even more amazing when considered that this was during a deeply christianizing age. Such a project was highly dangerous for this late and quite excellent philosopher, yet he managed to accomplish what was desired of him by the Gods.

He was also a major contributor to theurgical matters, rising to become the Head of the Platonic Academy. The Lycian philosopher wrote many interpretations and commentaries on Plato and Aristotle, considering himself a major link to and ceaseless advocate of their hidden doctrines.

EARLY LIFE

Proclus was born to a very wealthy Lycian family of some note. His parents were patricians who lived in Constantinople, the capital of the increasingly christianizing Empire. Despite his family's incredible wealth, he was noted to never use this wealth for any undesirable or ugly means. His physical fortitude and athletic greatness was such that he claimed to only have been sick twice in his entire life. One of the times he was sick he was visited by a God, Telesphorus, in the form of a beautiful fair child who touched his forehead and cured him of his ailment immediately.

One of his greatest influences was his mother Marcella who supposedly provided him with much of the moral and intellectual virtues that he would go on to cultivate strongly. His mother was stated to have many of the same qualities as Proclus and was marked out as an exceptional woman of her time.

It is said that Proclus was ordained in philosophical study because the Goddess Athena appeared to him in a dream guiding him towards the pursuit of excellence in thought and to use his mind for greater ends, a matter that he took up happily as an exercise of the mind.

He spent much of his youth attending a grammar school and then began study under the great extant philosophers of Alexandria. One of these, Isauros, was so impressed by the moral fortitude and great inner beauty of the young man that he invited him to become a house guest and not just a student at his school. Another of his teachers was Orion, a descendant of Egyptian high priests who was a great rhetorician and grammarian of his time.

PRIEST OF ATHENS

Having the most pleasant personality and rarely cultivating rage, anger or dispute, he was a paragon of the times. When he came to Athens, he hunted down all of the works of Aristotle and absorbed them systematically within two years. Following on from this he studied and unveiled many of the mysteries of Plato, conferring with Platonist philosophers to attempt to create a systematic doctrine. His teacher, Syrianius, was his closest friend; the two were even buried together with the same memorial.

Later, he assisted magistrates and ruling councils peaceably with suggestions that would be of greatest benefit for all. In spite of his pleasant personality, Proclus unfortunately lived in the age of the Christian ascendancy and soon attracted enemies, both religious and political. Firstly, he contended with the arrogance of many of the rulers. Secondly and severely, he was the object of certain plots against him by Christians who were outraged that he displayed many of the virtues that they claimed to have, and therefore they endeavored to endanger his life and to seize the large amount of wealth he had inherited.

One of these plots the Gods informed him beforehand was brewing dangerously, and so in not wanting to attract attention, he departed to Asia Minor, to the region of Lydia, where he learned many of the advanced theurgical rites passed down from generation to generation in secrecy.

Upon his return to Athens, much like Plotinus before him two centuries earlier, Proclus became beloved by many of the people of the city as a philanthropist and a great father to all believers. He was known to mediate disputes, assist the poor and the innocent and to bring families together.

After his vision of Athena as a child, pointedly he was a follower of the Goddesses to the strongest decree. One of his books, On the Mother of the Gods, made a name for itself as a treatise on the Goddesses. He particularly observed the rights of the Great Mother (Cybele) openly and clearly.

Whenever bad things occurred, Proclus met such matters with magnanimity and optimism. He was known to say: "Well, such are the habitual accidents of life!"

However,

his benevolence to others showed in the ways he utilized the Magick of the Gods, even healing sick children miraculously:

If we wished to do so, we might easily extend our observations on the theurgic labors of this blessed man. From among thousands, I will mention but one, which is really miraculous. One day Asklepigenia, daughter of Archiadas and Plutarche, and [now] wife of our benefactor Theagenes, being still small, and being raised at her parents', became ill with a sickness pronounced incurable by the physicians. Archiadas was in despair, as the child was the family's only hope, and naturally uttered distressful lamentations. Seeing her abandoned by the physicians, the father, as in the gravest circumstances of life, turned to his last resort, and ran to the philosopher's, as to the only person who could save her, and urgently besought him to come and pray for his daughter. The latter, taking with him the great Lydian Pericles, who also was a genuine philosopher, ran to the temple of Asklepius to pray to God in favor of the patient, for Athens was still fortunate enough to possess it, and it had not yet been sacked [by the Christians].

While he was praying according to the ancient rite, suddenly a change manifested in the little girl's condition, and there occurred a sudden improvement,----for the Savior, being a divinity, swiftly gave her back her health.1

It was often his presence that actually frustrated many of the designs of Christianity in the City of Athena itself, known as a distinct outpost of the worship of the Gods up until the time of Justinian. He was prolific in his work ethic and taught five times a day in addition to endless recitation and visiting various families to solve disputes. If there is anyone who could be considered a model priest, he fit the bill. It is known that even though he would have made a great ruler, he scorned any kind of political aspiration as to resemble the Gods.

How fondly Proclus was to the Gods is shown by this anecdote:

When the statue of the Goddess Athena was removed from the Parthenon [by the Christians], the Goddess appeared to Proclus and said to him:

"They turned me out of my Temple, now I come to live with you."Since then She lives in our homes and in our hearts.

LIFE OF PROCLUS

He is known to be an author of many tracts that were prevalent in late Antiquity. Proclus was so modest in his orientation that he did not even claim ownership of many of these tracks nor attempt to gain money from their publication. These tracks continued to be famous well into the Middle Ages and in fact unlike many pagan philosophers, he continued to cultivate a strong reputation in the enemy-led civilization.

Proclus’s contemporaries knew he had genuine theurgic powers. Marinus relates several miracles performed by Proclus through theurgy. For instance, during a severe drought, Proclus “had the power of producing rains by activating, at the right time, a particular rite,”

thereby delivering Athens from famine

THEURGY

Consequently, theurgy was a study area that Proclus invested much time and effort into, attempting to unveil the mysteries of the Gods:

He already possessed and practiced these virtues when he was still studying with the philosopher Syrianus, and while reading the treatises of the ancient philosophers; from his master's lips he had gathered the primary elements, and so to speak the germs of the Orphic and Chaldean theology. But Proclus never had the time to explain the Orphic poems.

Syrianus had indeed planned to explain to him and to Syrian Domninus, either one of these 42 works, the Orphic writings or the [Chaldean] Oracles, and had left the choice to them. But they did not agree in choosing the same work, Domninus choosing the Orphic, Proclus the Chaldean. This disagreement hindered Syrianus from doing anything, and then he soon died.

Therefore, Proclus had received from him only the first principles; but he studied the master's notes on the Orphics, and also the very numerous works of Porphyry and Iamblichus on the Oracles and other kindred Chaldean writings. Thus imbued with the divine Oracles, he achieved the highest of the virtues which the divine Iamblichus has so magnificently called the 'theurgic.' So Proclus combined the interpretations of his predecessors into a compendium that cost him much labor, and which he subjected to the most searching criticism, and he inserted therein the most characteristically Chaldean hypotheses, as well as the best drawn from the preceding commentaries written on the Oracles communicated by the divinities.1

Proclus held to Iamblichus’ belief that theurgy was an elevation of man into states of Godly consciousness and being, a matter of union with the Gods that they themselves instilled into humanity as a goal. He was also consciously aware that Christians began certain practices such as ‘Mass’ to attempt to mimic this in a powerless and pathetic manner that relied on props and intimidation.

He placed even greater emphasis on theurgy than his predecessors, considering it the indispensable means of salvation for the soul. Marinus, Proclus’s biographer, reports that Proclus achieved

“a still greater and more perfect virtue, namely the theurgic, passing beyond the theoretic”

level. In other words, Proclus regarded theurgic practice as the

consummation of the philosophical life, a stage of spiritual virtue higher than any attainable by study or dialectic alone.

One of his theurgical works, On the Hieratic Art of the Greeks, is an elaboration of symbolism.

PLATONIC THEOLOGY

Proclus most famous and dense work is the Theology of Plato. This is a somewhat difficult work of highly advanced caliber. In essence, it is an expanded interpretation of Plato’s Parmenides dialogue in particular and other dialogues secondly, hinting that the Parmenides contains many hidden meanings and layers about the nature of the soul and operations of the Gods in the elaborations of Socrates.

In the first parts of the book, Proclus lays out his interpretation that the soul has various powers for thinking, perceiving, and desiring. It is more fundamental than the physical body and depends on a higher intellectual realm.

The soul is inherently active and self-moving, giving life and a sense of movement to bodies. It has a strong connection to intellect and can gain knowledge of higher realities, including the divine, and it is considered divine and immortal in various degrees. It is subject to purification and has a potential for union with the divine.

He also argues for a principle that transcends both unity and multiplicity, suggesting that all beings must participate in 'the One' to have being. He further investigates whether this first principle is essence, intellect, or something beyond these factors, drawing upon Plato's dialogues, particularly The Republic and Parmenides, to support the idea of a transcendent 'Good' or 'One' that is the ultimate cause of all.

Ultimately, this section aims to establish a coherent theological framework based on Platonic thought. It posits the first principle that is ineffable, beyond being, and the source of all reality.

From this he engages in a separation of the life into three segments or Monads consisting of essence, life and intellect, as well as the Gods presiding over the intelligible and intellectual spheres of life. Proclus also discusses the extreme complexity of the triad of Jupiter, Saturn and Truth.

In the final part of the book, Proclus delineates in a complex manner the divisions of reality of the Twelve Gods, going further into intricate Astrological-Theurgical delineations of powers associated with planetary deities.

LEGACY

Proclus’ theology made its way into the Middle Ages, becoming popular as one form of escaping Christian misery. Much like Plotinus, many of his doctrines also found their way to the Islamic world as Aristotelian or Platonic texts thought to be by either of those authors. He also influenced Plethon to formulate his own theology many years later.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Life of Proclus, Marinus

Life of Proclus, Roy George, goddess-athena

Theology of Plato, Proclus

CREDIT

[TG] Karnonnos

አማርኛ

አማርኛ العربية

العربية বাংলা

বাংলা Български

Български 中文

中文 Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Deutsch

Deutsch Eesti

Eesti Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Español

Español Français

Français हिन्दी

हिन्दी Hrvatski

Hrvatski IsiZulu

IsiZulu Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 Kiswahili

Kiswahili Magyar

Magyar Македонски

Македонски नेपाली

नेपाली Nederlands

Nederlands فارسی

فارسی Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Slovenščina

Slovenščina Suomi

Suomi Svenska

Svenska Tagalog

Tagalog Türkçe

Türkçe